Behind the Lens

Irving Penn: Capturing Timeless Beauty and Defining Fashion Photography

Published

11 months agoon

Irving Penn (1917-2009), who detested being photographed himself, once said, “I myself have always stood in awe of the camera. I recognize it for the instrument it is, part Stradivarius, part scalpel.” He handled both parts brilliantly, producing exquisite tones and making his cuts with finesse and precision. He was speaking about portraits, for he went on to say that he did not consider it cruel “when I seek to make an incision in the presented façade…Very often what lies behind the façade is rare and more wonderful than the subject knows or dares to believe.” But both parts of his instrument were constantly in play. He had a virtuoso’s command of widely varied beauties and moods – though the tempo was almost always adagio, even glacially still – and his scalpel was continually in use. He cropped in the viewfinder and afterward, and he rigorously cut out everything extraneous: backgrounds, props, gestures, foreheads, anything, everything. “For me,” he said, “the process of photography is a pruning process. Taking away what’s not necessary… Painting is an additive process, photography is a subtractive process.”

But painting was his first great and overwhelming ambition. From 1934 to 1938, deep in the Depression, he attended the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, drew from plaster casts and live models, learned the techniques of water color and oil, and chose Alexey Brodovitch as his major instructor. Brodovitch, the legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar, through his design courses and later photography classes, influenced such photographers as Richard Avedon, Hiro, Lisette Model, Diane Arbus – and Irving Penn. He encouraged Penn’s design work and invited him to be his assistant at the magazine during two summers and to work with him on several personal projects. Occasionally, Brodovitch asked Penn to make small drawings, a few of which were published in the magazine. Penn was barely out of his teens.

For many years, aspiring artists yearned to be painters the way mountain climbers yearn to conquer Everest and little boys yearn to be president (or firemen). Though he had no intention of being a photographer, Penn bought a Rolleiflex as an aide mémoire with the money he earned from his drawings, and in fact he took photographs that already showed his strong sense of composition and graphic design. But what he wanted deep in his heart was to earn the honorific “painter.” In 1941, when he was working as an art director at Saks Fifth Avenue, the kind of job his art school classmates considered a stepping-stone to heaven, he quit to spend a year living on meager means in Mexico to devote his life to canvas. Irving Penn had determination bordering on obsession in his bones, determination to be the best he could and perhaps simply the best. This was coupled with a nagging uncertainty that he could reach that pinnacle, an uncertainty he never quite put to rest. That may be one definition of perfectionism, which he wore like a glove; one observer says he was not easy to work with, and “even objects had to comply” – when an assignment was to show the instant a tray full of glasses fell, he insisted that all the glasses, in all the trial shots, be Baccarat. Yet Penn’s steely determination drove past his insecurities onto high ground over and over again. He judged himself strictly: at the end of that year in Mexico he decided he wasn’t good enough to live up to his own standards, and he took his linen canvases into the bathtub and washed off every trace of not-good-enough. Later, he sometimes used his erased paintings as tablecloths.

When he returned from Mexico, Alexander Liberman, another extraordinary art director, hired him as an associate at Vogue. Penn did layouts and drew cover designs for photographers, who neither liked nor followed them. At length Liberman, who had seen some of Penn’s photographs, suggested he take them himself. Penn’s first Vogue cover, in 1943, was a color still life, the magazine’s first still-life cover. In 1944, Penn volunteered for the American Field Service, driving ambulances and taking photographs overseas until the end of the war. He then returned to Vogue and immediately began taking fashion pictures, still lifes, and portraits.

He was a modest man, private, formal, rather shy, and reticent. He spoke so softly that at times one might have been grateful for an ear trumpet. Scarcely the Hollywood profile of a revolutionary, even a revolutionary artist– yet by 1947 he had sweepingly revised the traditions of both fashion photography and portraiture (more on portraits later), and in time he would toss in the resurrection of a nearly-forgotten process as spare change. He began by throwing overboard all the standard procedures. Fashion photography in the 1930s, influenced by Edward Steichen and European sources, tended toward a cinematic and dramatic lighting, with elaborate poses and gestures, cleverly designed backgrounds, and suggestions of theatrical situations or narrative. Penn wiped the slate as clean as his linen canvases. His fashion photographs were exceedingly simple and pared down – context, story-telling props, and extravagant artifice had been removed as if by a scalpel in the hand of a surgeon intent on removing moribund tissue to reveal clean skin.

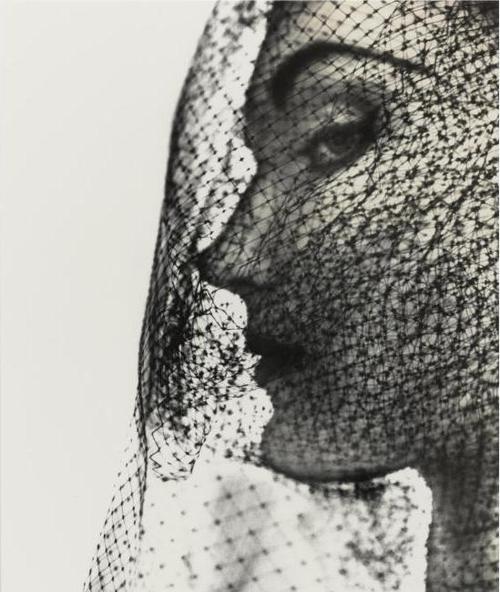

His light was soft, even, and clear, more like the liquid light of day than the strong light and hard-edged shadows that were de rigeur in fashion magazines. For years Penn daydreamed about a studio with a northern skylight letting in the light of the outdoors; the kind of light that nineteenth-century photographers worked with. In 1946-47 he designed a bank of tungsten lights on a ceiling track to approximate a skylight.8 Behind most of his fashion models was a gray and lightly mottled wall or a plain white sheet of paper setting off the stark blacks of clothing. In 1950 he would carry this kind of contrast to its logical, striking conclusion: a picture of Jean Patchett in a black jacket, white scarf and gloves, a black hat with a white band around it and a black veil. The image, without modeling and only a few tiny and faint shadows, was set against a bare white ground on the cover of Vogue, where all the type was black, and the model looked off to the side as if to avoid the photographer’s stare.

This bold graphic approach was particularly apt for the simpler, pragmatic clothes designed by young Americans conscious of shortages brought on by a world war and the new freedom women had found during that conflict. But the fashion world, having never seen such images, was up in arms; some vehemently against, some equally for. “For the first few years,” Liberman said, “Penn and I were thought of as dangerous destroyers of good manners in a world of ladies in status hats and white gloves.” It was not the first time and it would not be the last that an assault on good manners would change the manners themselves: in a few years magazines adopted Penn’s light, and for a while some photographers imitated his brash simplicity, never quite achieving his audaciously minimal elegance.

The first postwar years were a time for fresh beginnings, and Penn and Richard Avedon, Penn’s only real rival and equal at the time, both changed the temperature of fashion photography in highly individual ways. Avedon employed white backgrounds in his own manner to great stylistic success. When he photographed the Paris collections beginning in 1947, he took his models outside to street performances and set them in motion, descending stairs in swirling skirts that the French, after lean years, at last had sufficient fabric to create. When Vogue sent Penn to photograph the collections in 1950, he was delighted to spend his days inside an old daylight studio with a discarded theater curtain bearing all the marks of age upon it for backdrop.10 His pictures were immensely still; occasional stances and gestures wrote temperamental lines across the surface. His models were engaged in no activity but modeling and no encounter with anyone or anything but the camera; they were isolated within the proposition of displaying two objects of beauty and desire: the couture and themselves. Penn, an exacting craftsman, understood and communicated the delicacies of couturier design and dressmaking. He photographed fashion excerpts and minutiae, like a voluminous, pouffed sleeve or a gauntlet with a diaphanous kerchief attached to it. Fashion photography, today more focused on life style, no longer takes close-ups of details very often, partly because the skills that produced such details are no longer available in quantity.

In Paris Penn took one of the lasting icons of fashion photography, the picture of Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn – he married her in 1950 – in the Mermaid Dress, as well as other stunning pictures of the latest fantasies of female allure. The Mermaid Dress picture and a couple of others show the theater curtain’s edge and a bit of studio wall behind it, a signature mark of Penn’s, a reminder that the dress and make-up are not the only constructs; the studio and the photograph are equal players in that game. Penn was adept at undercutting the camera’s assumed realism and the carefully engineered seduction of his scenes when he wanted to, by saying, in effect, this is only a photograph, it’s a set-up, beware of being entirely taken in. Yet more intrinsic to his thinking is the fact that the curtain’s edge is irregular, a little rough, setting off the elevated glories of superb bone structure, figure, materials, and tailoring with a decidedly imperfect and evidently worn element – as if to say, “All good things must come to an end.”

This idea is key to Penn’s work and pervades it. Fascinated with entropy and preoccupied with decay, far more fascinated with the ultimate end of all things than with fashion, he injected reminders whenever he could into unexpected places. Fashion was in a sense what happened to him when he found work he could thrive on, but his curiosity was practically boundless. He once said to me, “I can get obsessed with anything if I look at it long enough. That’s the curse of being a photographer.”

When it came to faces and what he could find there, Penn (and minutes later Avedon) brought about what could fairly be called a revolution in studio portraiture by changing the nature of the relationship between photographer and subject. When Hollywood stars sat for Hollywood portraits in the 1930s, they expected to be turned into gods and goddesses of the screen, and so they were. Portraits of celebrated people in the immediate postwar years made a point of telling you who the sitters were or what they were famous for by referring to their work or their work spaces. Writers, artists, politicians, the famous of every ilk expected to be, and were, shown as the best of what they were and the best of themselves. People went to a studio to be flattered; it was their due. Penn turned that on its head.

He once made out a list of people he’d like to photograph; decades later he recalled, “I was shivering at putting these gigantic figures on a list.” His portraits removed identifying context and substituted for it two simple, unprecedented, inelegant, and psychologically charged settings. In 1947 he began with a rug he’d picked up when he passed a junk shop, one of those items that pleased him with its evidence of wear and tear and intimations of ultimate disintegration. Distinguished people came to lean on it, sit on it, drape themselves over it. Alfred Hitchcock looked like an overstuffed bag that had sprouted a suspicious head (Janet Flanner wrote Penn that this portrait “is a fine piece of monstrosity, practically straight Goya.”)13 George Jean Nathan and a world-weary H. L. Mencken were half hidden behind the rug, each with a hand to his chin and one of Mencken’s hands advancing between them as if it belonged to both. Christian Dior slumped on the rug like an empty sack, his head nodding off to one side, his body and legs weightlessly vanishing into blackness. These were (and still are) arresting pictures, as nothing quite like them had been seen before.

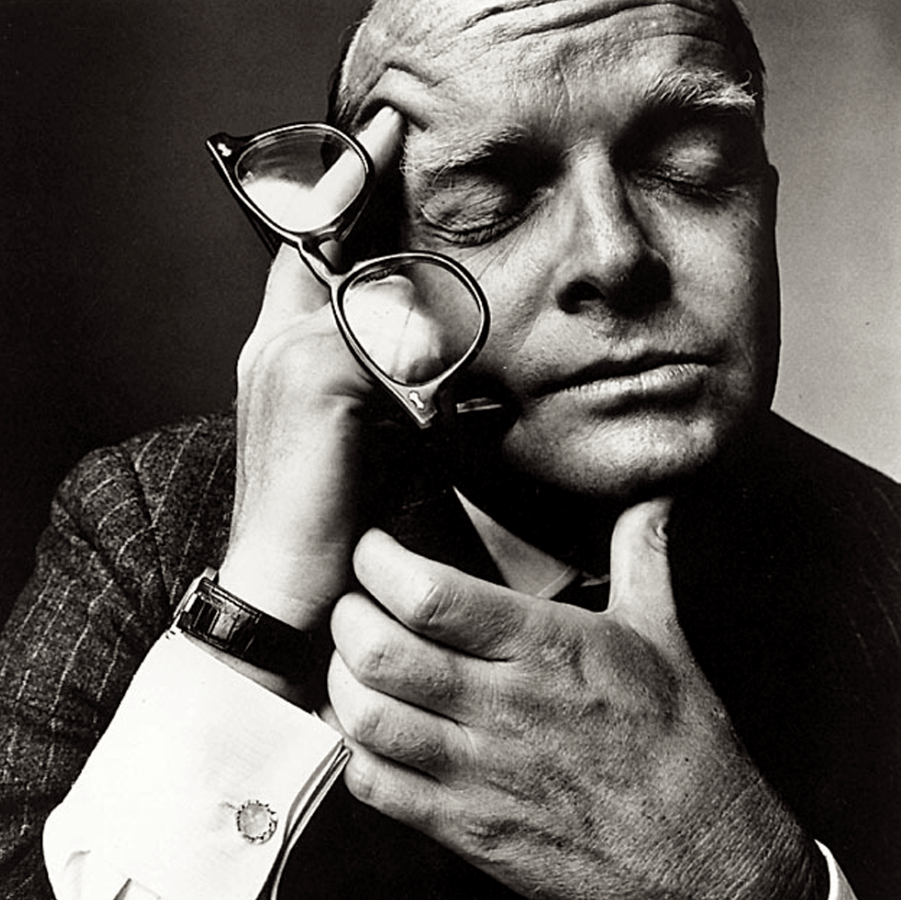

Penn also built a narrow corner from two studio flats and let subjects arrange themselves as they would; he said he invented it because he felt unequal to his famous subjects.14 Some of these images pull back to reveal the rough edges of the flats, emphasizing yet again the contrivance of the photograph and the imperfection of the means. Individuals reacted to this tight spot in individual ways. Marcel Duchamp leaned back comfortably against the corner with a little smile, George Grosz leaned forward anxiously in a too-small chair in this too-small space, Truman Capote knelt on the chair and huddled defensively in a coat that was so much too large it utterly defeated his body. (Penn photographed him again years later as a thoughtful man whose eyes are nonetheless closed to the camera and anything else worth seeing.) Georgia O’Keeffe shrank so deeply into the corner she seemed to be shriveling away. These people were in a tight spot and literally cornered, potential prey to all the anxieties left over from a war and a bomb that changed the world. They were also irretrievably alone, with no one to communicate with but the photographer. Penn said he didn’t direct them or make “very small talk” but might say something like, “How does it feel to you if you realize this eye looking at you is the eye of 1,200,000 people looking at you…?”

Penn flattered his models but not his heroes. He thought of himself as neutral, attempting to cut through the façade and find something the subject might not even realize was there. He felt not a shred of obligation to make his subjects attractive. Angry letters filled his mailbox. Georgia O’Keeffe so hated her portrait that Penn never published it in her lifetime. But he was not working for O’Keeffe or anyone else before his lens but for a magazine’s pages. He defined the largely unacknowledged but bedrock difference between a portrait commissioned by the sitter and one commissioned by a magazine: “Many photographers feel their client is the subject,” he said. “Karsh does. My client is a woman in Kansas who reads Vogue. I’m trying to intrigue, stimulate, feed her. My responsibility is to the reader. A severe portrait which is not the greatest joy in the world to the subject may be enormously interesting to the reader.”17 And in a sense his real obligation was to his very demanding self, to make the finest picture he could make, the devil take any lurking vanity.

His portraits were not only stunning, many of them enduringly so, but they opened the door to the kind of celebrity portraiture so familiar since the 1960s, distinctly unflattering but distinctive pictures which at length devolved into just-get-my-face-in-the-media-and-the-rest-doesn’t-matter photographs. Abroad in 1950 without his corner set-up, then back home later, Penn moved in extremely close to T.S. Eliot, Richard Burton, Henry Moore, Colette, Picasso. Picasso’s face was so deep in shadow and buried in a pulled-up collar and a pulled-down hat that all that emerged was barely half his nose, an ear, and a single burning eye. Colette was eighty and confined to bed; her husband said the picture “was a startling image, but was also an act of treachery, an intrusion upon her inmost being. It laid bare all that Colette liked to conceal – and doubtless something about herself of which not even she was aware…” Sometimes Penn got so close he cut off foreheads (see the sad face of S.J. Perelman, the writer of wittily amusing stories), and sometimes he placed his half-length subjects behind a table as if they were speaking to us at an uncomfortably close distance. Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert H. Grosvenor (he was the editor of National Geographic) sat behind such a table, he in bow tie, waistcoat with chain, and disapproving look, she with crimped white hair, wrinkles, and an air of caution, the picture a kind of upper-class Wasp version of American Gothic.

Penn was at least as interested in the lower strata of society and in less sophisticated societies in general as he was in the upper crust of adornment, good looks, or achievement. In 1948, when Vogue sent him to Peru for a fashion spread, he stayed on in Cuzco to photograph the inhabitants. He discovered a daylight studio and got helpers to bring country people to his door. Unaccustomed to posing, some of them even unaccustomed to cameras, they shook with nervousness and went rigid with fear. Penn posed them by hand with difficulty. He presented them centered and before a mottled gray backdrop, as formally arranged as any of his fashion models. Shoeless or tattered, they were entirely self-possessed, often with chins proudly lifted, in their hand-woven, multi-layered winter garments. Two barefoot children with raggedy clothes and adult faces hold hands upon a small table between them; a kneeling man steadies his imperious little girl on a table; three men sit on the floor, wrapped up in striped blankets and knitted face masks against the cold. Penn was surprised and touched when many of those fearful subjects turned up again the next day.19 Did they come for the money he paid them? Certainly, but the close and serious attention to themselves may have counted too. Penn spoke of certain unsophisticated subjects as being transformed when they came into the studio. Lionel Tiger, a sophisticated anthropologist, wrote about being photographed by Penn that he’d had a feeling “of giving more than I had, of being more than I was, of telling more than my story.”

In Paris in 1950, when Penn was photographing haute couture and celebrities, Liberman suggested that he make portraits of workers in the petits métiers, the little trades. The petits métiers, particularly characteristic of Paris, had been slowly disappearing for years; Parisian photographers like Atget and Brassai occasionally photographed those still at work on the streets. Vogue hired Robert Doisneau, who photographed all the nooks, crannies, and denizens of Paris, to find subjects for Penn, who didn’t know who Doisneau was. Penn posed a glazier, a coalman, a news vendor, a waiter, in their working clothes, full length before his favorite dappled backdrop, much as he had his fashion models, and was so captivated that he went on to photograph the little trades in London and New York – a rag and bone man; a sewer cleaner; a New York street photographer in a long coat beside a large-format camera on a tripod, looking like he might almost have walked in off a nineteenth-century sidewalk. Penn said the Parisians were suspicious but came for the fee, Londoners were proud, but the Americans were unpredictable: “In spite of our cautions, a few arrived for their sitting having shed their work clothes, shaved, even wearing dark Sunday sits, sure this was their first step on the way to Hollywood.”

All of these workers, beautifully lit with strong shadows on their faces and their dark clothes seldom admitting much modeling, stand tall and are often in bold poses. There have been times in painting and photography when full-length portraits cost more than half-length and under the circumstances favored the well born; the tradesmen, poised in the center with their accompanying implements, are as dignified as any aristocrat. Indeed, before the lens they have become aristocrats of their professions: entirely self-assured, even prepossessing, no matter what their gear or shabby clothes.

Penn could focus easily on widely varying subjects one after another, in part because he could become wholly absorbed in such a wide spectrum of things and people when he was behind his camera, in part because he seems to have regarded people from entirely different backgrounds and stations as equally interesting, possibly even equal. Certainly he took similar approaches to almost everyone who posed before him.

His interest in the lower echelons of society (and what might be called the lowest echelons of objects, which would later enter his still lifes) precedes his career. The photographs he made in the late 1930s and early 1940s, before he was a photographer, are very much of a time when photographers set out to witness a Depression, paid attention to people at the bottom of the economic ladder, and noticed how signs and advertising had become an environment as surely as paved streets had. He photographed poor blacks in the South and signs that were mostly hand-painted, “vernacular” notices, some of them missing letters or flaking off.

When it came to objects, he could make watermelon and gold watches as tantalizing as wishes, but his still lifes for Vogue alsomake clear that he valued the intrusions of everyday life into the carefully arranged paradises of commercial photography. “I began with still life,” he said, recalling his 1943 cover. “I didn’t have any sense of strength to deal with human beings at the time, either personal or photographic strength.” John Szarkowski, who curated a large Penn exhibition at MoMA in 2001, wrote that he couldn’t find any still lifes in earlier issues of the magazine and thought Penn probably introduced the genre to fashion magazines. Luscious in color, and generally luscious in black-and-white as well, Penn’s idylls of fruit and wine glasses, compotes and torn loaves of bread are anchored by gravity but often with only a nominal indication of a table to rest on. Then there are the intruders: a fly sits on a blazing yellow lemon; a charred match and its ashes lie by a perilously balanced composition of playing cards, dice, and poker chips; broken off cherry stems and a small beetle join the Elements of a Party. The results are a version of classicism with a view toward misrule and debility. He also photographed flowers for Vogue, magisterial red poppies and purple tulips heraldically set off by white backgrounds; afterwards, he photographed them as their petals wept their way to the ground on the path to death.

In Summer Sleep, a young woman, asleep beside a fan, a coffee cup, a piece of fruit and a fly swatter, is seen through a screen that flies crawl over – Penn affixed them, dead, to the outside of the screen with great care. And in The Empty Plate, an editorial photograph for House & Garden in 1947, the napkin is as crumpled as a piece of foil and the plate is full of food spatters, some of which have migrated to the table cloth. (Penn preceded artistic explorations more than once. The attitude toward food in The Empty Plate would be taken even further by Daniel Spoerri (who probably did not know Penn’s photograph), in the 1960s, when he hung on a gallery wall the remains of a meal eaten by Marcel Duchamp.) In Penn’s late still lifes for Vogue, in the 1990s, the objects themselves, rather than the leftovers or incidental intruders, could be disturbing – skinned frogs’ legs, an oozing oyster – and served up floating on a blank white page.

The unwelcome participants in the still lifes have some reference in seventeenth-century Dutch paintings where occasional insects, broken glasses and obvious memento mori like hour glasses remind us that these things too will vanish with time. Yet the mainstream of still life in the twentieth century – cubism’s pitchers and guitars, Giorgio Morandi’s bottles, Edward Weston’s peppers – was far more appreciative then premonitory. Penn was once again contradicting tradition.

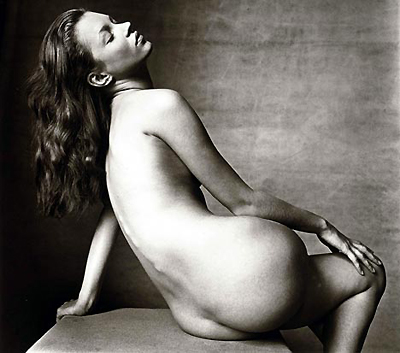

At the end of the 1940s, Penn made a series of nudes, using fleshy artists’ models, most distinctly unbeautiful (at least by conventional standards), all anonymously headless: the imperfect world in place of the manufactured dream of beauty in Vogue. Some were in contorted or ungainly poses or arranged like near-abstract sculptures. A decade later, when magazine production values had declined, he decided to print these pictures in platinum, once valued for its subtlety and artistic qualities. But platinum paper had not been manufactured for years, and the technique was virtually forgotten. Determined as always, Penn spent hours scouring the library and many more hours in the darkroom; by the late 1960s he had revived and elaborated on an outmoded tradition and an almost-vanished technique. The nudes were first shown in 1980; the postal restrictions in 1950 would have prevented their being published back then.

In the 1970s, Penn, smitten with the look of people from distant cultures and keen to photograph them, devised a traveling studio and took it to places like Morocco, Dahomey, Nepal, and New Guinea. He photographed people in their native costumes and posed them once more like his fashion models or celebrities, in the center of the picture against a washy gray ground, without props except for the weapons some carried. In Africa and New Guinea, the clothes, whether minimal or maximal, and the jewelry, feathers, nose ornaments, wigs, ornamental cicatrices, masks, and face and body paint were not merely strange to western eyes, but complicated, intricate, extravagantly artistic. The pictures were severely criticized. Penn was accused of treating native people as if they were outlandish fashion plates, exploiting them as the exotic Other. Penn explained his preference for studio photography over reports of daily life, saying he “had even developed a taste for pictures that were somewhat contrived. I had accepted for myself a stylization that I felt was more valid than a simulated naturalism.” He also noted that modern life so efficiently dissolved cultures that his photographs would become documents and preserve some part of a vanished world.

The anthropologist Edmund Carpenter had another thought, that these images not only “enlarged membership in the world community,” but they also “record a major change in human identity,” when people who had never seen themselves suddenly did so.”24 Carpenter also threw a raking light on the vexed issue of documentation. Penn made a photograph of Three Asaro Mud Men of New Guinea, 1970, armed with bows, arrows, and threatening mud masks. He posed his subjects by hand, as he didn’t speak their language, and discovered that in this culture, if you touched someone, that was regarded as an embrace and elicited a hug in return: “It’s a picture made up of a lot of double embraces.”25 Penn also related that “the masks recall a battle in which their remote ancestors, driven into a river by an enemy tribe, emerged mud-covered. Their attackers, thinking them evil spirits, turned and ran.”26 Carpenter, however, says the mud men were “invented” by Trans-Australian Airlines, which scheduled a lunch stop for a busload of tourists at a village halfway to their destination. Since there was no entertainment in that village, the airline designed costumes and dances that convinced tourists, a photographer, and generations of photography lovers that they had witnessed authentic native culture.

Penn’s work, which sparked debate the moment he started in fashion photography, continued to generate controversy. In 1975 the Museum of Modern Art exhibited his platinum prints of discarded cigarette butts, and two years later the Metropolitan Museum showed his platinum prints of urban debris; both caused what passes for an uproar in critical circles. Some thought art museums had no business showing work by a fashion photographer, others that the images were pretentious; still others questioned whether it was appropriate to record street trash in precious metal. Yet it would not be long before museums would be hanging fashion photographs on their walls and hosting an array of street trash in scatter-art installations. Once again, Penn was early. Artists would soon be replicating everyday objects in expensive metals, and the art vs. commerce conflict would begin to fade as the distinctions between high and low art were erased.

The cigarette butts, photographed vertically and monumentally as if they were crumpled and afflicted trees, and the run-over gloves and paper cups dredged up from the street, continued Penn’s career-long obsession with decay and death. Objects, too, suffer the universal law of mortality. A series of still lifes made several years later from pitchers, chunks of discarded metal arranged in precarious balance, bits of bone, and human skulls –perhaps not Penn’s most authoritative work – make the message unmistakable. Penn had long ago erected a barrier against the uncontrollable forces of entropy: a style of delicate balance and near-perfect elegance. “The world is only chaotic,” he said; “for me, the process is to bring order.”

But he repeatedly acknowledged that the laws of the universe trumped artifice, that insects would invade the most magnificent fruit bowl, that objects wore out, that time, disorder, and death won every match. As Robert Browning put it, “What’s come to perfection perishes.” And Issey Miyake wrote in the book of dazzlingly inventive photographs Penn took of Miyake’s clothing designs, “Maybe the really creative person is someone with a little touch of poison. Or a lot of poison.”Or a knowledge of the bitter taste of death.

Vicki Goldberg, an American photography critic and historian, resides in New Hampshire, USA. With expertise in the field, she has authored books and articles exploring photography’s social history and its impact.

You may like

-

Between Dreams and Reality: The Surreal Artistry of Miss Aniela (Natalie Dybisz)

-

REVIEW: Play the Part: Marlene Dietrich

-

Through the Lens of Tragedy: The Final Frames of Gilad Kfir, Photographer and Aspiring Father

-

TOMAAS: Bridging Realms of Surrealism and Post-Humanism

-

Yigal Pardo: A Visionary Alchemist Redefining Photography with Surreal Enchantment

-

Transcending Boundaries: The Multifaceted Artistry of Igor Shrayer